‘A Sense of Place’: Three 2023 Goldman Environmental Prize Winners Protect Their Homes

Why you can trust us

Why you can trust us

Founded in 2005 as an Ohio-based environmental newspaper, EcoWatch is a digital platform dedicated to publishing quality, science-based content on environmental issues, causes, and solutions.

On Saturday, we celebrated our mother Earth. Now, it’s time to celebrate the human beings who defend her.

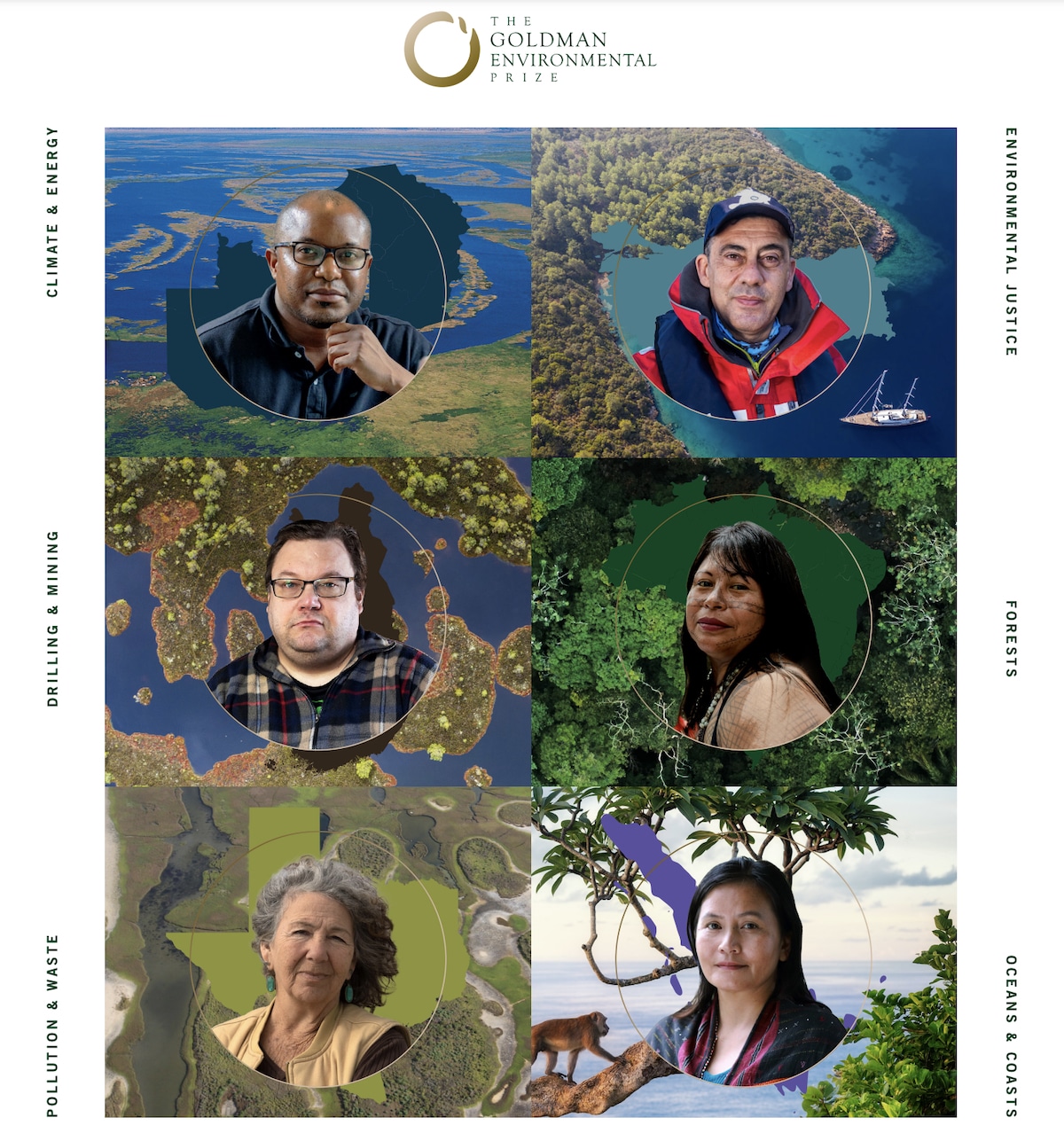

The 2023 Goldman Environmental Prize winners — chosen from all six continents for their grassroots environmental activism — were announced Monday and will be formally celebrated at the San Francisco Opera House at 5:30 p.m. Pacific Time.

“Now that the world has awakened to acute environmental crises like climate change, fossil fuel extraction, and pollution of our air and water, we are much more aware of our connections to each other and to all life on the planet,” Goldman Environmental Foundation President John Goldman said in a press release shared with EcoWatch.

For the first time since 2019, this afternoon’s ceremony will be held in person. But you can also watch from wherever you are via the Goldman Prize’s YouTube channel. Ahead of the ceremony, EcoWatch had a chance to speak with three of the winners and learn how their efforts to protect and restore their own beloved ecosystems connect to the global struggle to preserve our shared home.

Delima Silalahi: ‘We Live From That Tree‘

Delima Silalahi is a Batak woman who was born and raised in a rural part of northern Sumatra near Lake Toba.

“It used to be a beautiful forest, beautiful rivers when I was growing up,” she told EcoWatch through a translator.

However, in the last three decades — Silalahi is now 46 — she noticed a change. Large pulp and paper mills, in particular Toba Pulp Lestari (TPL), began to clear biodiverse rainforests and plant monoculture eucalyptus plantations in their place, destroying the trees and rivers she’d known as a child.

“Everything is almost gone,” she said.

This destruction has global consequences. Indonesia comes in third for the amount of rainforest in a single country, yet deforestation has tipped the region from a net carbon sink to a source of global heating, and land-use change is the main reason why Indonesia is among the top greenhouse gas emitters. Between 2015 and 2019, it lost an area of forest and peatland to fire that was larger than the Netherlands.

Silalahi first got involved with efforts to stop this destruction in college, and joined the NGO Kelompok Studi dan Pengembangan Prakarsa Masyarakat (KSPPM) as a volunteer in 1999. Her and KSPPM’s efforts to preserve the remaining forest got a boost in 2013, when the constitutional court ruled that customary forests that had been traditionally managed by Indigenous peoples were separate from state-owned forests, giving the Indigenous Tano Batak people of northern Sumatra a chance to legally claim the forests in which they had long built their lives.

However, Silalahi explained, “this law mechanism that we’re trying to use for our fight is very complicated.”

Indigenous people tend to rely on oral history, and Silalahi and her team at KSPPM had to help them translate this spoken tradition into written documentation of their claim, as well as empowering local communities to take on a leadership role in the effort. At the same time, land defenders in Indonesia — as in many other parts of the world — are often criminalized for their efforts, and TPL has a history of calling the police on people who protest its activities.

In 2022, all the risk and hard work paid off when the Indonesian government recognized the legal right of six Tano Batak communities to 17,824 acres of forest. This is good news for the communities and for the global movement against the climate crisis and biodiversity loss because in Indonesia, as in most of the world, Indigenous people are the best protectors of the land they inhabit. In Indonesia, Silalahi said, forests controlled by Indigenous people and local communities are “thriving” compared to state forests, since the government often grants concessions to extractive industries. The Tano Batak people, for example, know how to manage the forests sustainably to cultivate a particular tree — the benzoin styrax tree that produces a type of resin called the frankincense of Sumatra.

“That is actually our backbone of economy,” Silalahi said. “We live from that tree.”

The tree grows better in the shade of taller trees while surrounded by biodiversity, so by nourishing this tree, the Tano Batak people also protect the forest. Now that the six communities have legal control of the 17,824 acres, they plan to restore a 1,000-hectare portion that has already been cleared and planted with eucalyptus trees, find ways to pass the older generation’s knowledge of the forest down to younger members of the community and boost the economic vitality of the benzoin styrax forests. Silalahi is also hoping to help other groups secure similar victores.

“1,700 hectares is a very small portion of what we want to get back,” she said. “And there are a lot of tribal communities that are still fighting so hard to get their land back. And we’re hoping that the government will support our fights to save and preserve and to return these tribal lands back to the local communities.”

The Goldman Environmental Prize should help with these goals.

“It will strengthen the activism of the local people, and it will open their eyes that their work can be appreciated, and also that their work is not wasteful,” she said.

The Tano Batak want to save the forest to protect their livelihood. But the prize helps them see that they are also saving Indonesia and the whole world.

Zafer Kizilkaya: ‘Those Fishes Are My Friend’

When Zafer Kizilkaya went scuba diving in his native Turkey in 2007 after years of living and working abroad, he was shocked by how much the ecosystem had changed. The fish in Gökova Bay — once a biodiversity hotspot on the country’s Turquoise Coast — had disappeared.

“Something is going really terribly wrong here,” he remembered thinking.

Kizilkaya had loved the ocean since he was a child visiting the sea during the summer holidays. Growing up he had wanted to be a biologist, but his parents persuaded him to study engineering instead. However, in college he also learned to scuba dive and soon embarked on a career as commercial diver and underwater photographer, working for several years in Indonesia and the Pacific.

Back in Turkey, he decided to verify the results of his disturbing dive with research. He found that the number of fish in the area was the lowest in all of the Mediterranean at around four grams per square meter. At the same time, local small-scale fisheries collapsed.

“It was a kind of a sign for me, okay, let’s do something here,” he told EcoWatch.

What he did was start the Akdeniz Koruma Dernği, or Mediterranean Conservation Society, in 2012 and work with community fisheries to establish and enforce marine protected areas. This meant first convincing small-scale fishers that they would ultimately catch more fish overall if they left certain areas alone.

“All those protected areas are your savings accounts,” Kizilkaya would explain. “As long as you have savings accounts, you will have an interest.”

In this case, the interest was fish.

At first, convincing them was a challenge.

“Fishers are fishers all around the world,” Kizilkaya said. “They’re stubborn. They don’t want to be interrupted.”

Kizilkaya did have some friends in the community who understood his argument and helped to persuade their neighbors. Once the first marine protected area was established in Gökova Bay, however, there was another problem. As more and more refugees from the Syrian civil war and other Middle Eastern conflicts began fleeing across the Mediterranean to Greece in shoddy, over-crowded boats, the Turkish coast guard grew busy trying to rescue them and wasn’t able to enforce the boundaries of the protected area, turning it into a “paper park.”

So Kizilkaya and his colleagues bought their own speedboats and hired local fishers to patrol the park’s boundaries. At first, this led to conflicts as other members of the community would still try to fish the now off-limits waters.

“We had terrible cases at the beginning that rangers were fighting with their friends in the streets because they fined them for doing illegal fishing,” Kizilkaya said.

Soon, though, the community came together, and the results spoke for themselves.

“Just in three years there was a huge difference in protected areas in terms of fish biomass,” Kizilkaya said. “And at the end of the third year there was also a big difference in the catch.”

Target species began biting again, and in bigger numbers. The local fisheries were now so convinced of the value of their new savings accounts that they backed Kizilkaya’s efforts to expand the number of reserves along the coast.

“The small-scale fishers came to our meetings; they told their story that there are a lot of fish right now: ‘We didn’t believe this project at the beginning,’” they would say, as Kizilkaya recalled, “‘but we should do the same in other areas to get the same benefits.’”

In 2020, the Turkish government agreed to expand the country’s network of marine protected areas by 310 miles southeast along the coast, increasing the zone protected from trawling and purse seine fishing by 135 square miles for no trawling and no purse seine and the water protected from all fishing by 27 square miles.

Now when Kizilkaya, who is 53, dives or monitors the areas by camera, he notices the difference in biodiversity, including the birth of critically endangered monk seal pups and the consistent presence of sharks.

“This is my biggest joy, just going back to those areas every year and just counting the fish, seeing the increase, and also the different species,” Kizilkaya said, adding, “All those fishes are my friend.”

Kizilkaya hopes to expand his model of protected areas across the Turkish coastline and throughout the Mediterranean. He also has advice for world leaders looking to protect 30 percent of land and water by 2030, which is that they focus on enforcing protections in reality over meeting the goal on paper.

His Goldman Environmental Prize win bolsters his faith that more people are coming to understand the importance of effective ocean protection.

“That’s the kind of feeling that, okay, we are not alone, somebody is watching us from a distance, so we are doing something good,” he said.

Diane Wilson: ‘Sense of Place‘

Diane Wilson, the director and founder of Calhoun County Resource Watch and the executive director of San Antonio Bay Estuarine Waterkeeper, has lived and fished along the central Texas Gulf Coast for all of her 74 years. Before her, her family lived and fished there for three generations.

“I had a lawyer one time, and he said, ‘Wilson, you have what they call a sense of place,’” she told EcoWatch.

Wilson’s place in particular is where Lavaca Bay joins Matagorda Bay in Texas’s Calhoun County, an area she refers to as “the bay.” Wilson said her passion for this ecosystem has driven all of her activism.

“I really believe it has its own right for existence,” she said.

In her lifetime, she has seen that existence threatened by her region’s status as the most petrochemical-producing part of the country, earning it the nickname the “Cancer Belt.” She has witnessed dolphin die-offs and algae blooms and the depletion of a once robust shrimping industry.

“Now there are no shrimp houses. There are no shrimp boats,” she said.

In 1983, Formosa Plastics’ Point Comfort plant — the largest plastic plant in the U.S. — set up shop right along Lavaca Bay. Six years later, Wilson noticed her shrimping numbers plummet and began an investigation into the plant’s wastewater discharge that would continue in various forms for the next three decades. In 2008, a whistleblower at the plant drew her attention to nurdles — tiny plastic pellets that are the building blocks of petrochemical products from water bottles to car parts.

“I had this worker contact me, and he wanted to meet me actually in a beer joint called the Hideout, about 40 miles away,” she said. “And he started telling me about the pellets.”

In meetings with the company, Formosa denied that it had ever released any nurdles into waterways.

“I knew that was wrong because I had already seen them,” Wilson said.

At the same time, both Formosa and state regulatory agencies claimed the nurdles were harmless. This didn’t match with Wilson’s experience either. Lavaca Bay already hosts a mercury superfund site, and tests revealed that the toxic metal was sticking to the nurdles, which oystermen would find embedded in their oysters. Every piece of evidence that has come out since about the dangers of microplastic pollution has only bolstered her concerns.

“We have scientists who have already documented that there is a significant loss of biomass and bio-abundance in our bays,” she said. “And it’s not like anywhere else. It’s just around Formosa’s discharge.”

So Wilson, with her allies, spent four years documenting Formosa’s nurdle releases into the bay, locating source points via kayak, collecting more than 40 million nurdles and taking more than 7,000 photos and videos. When the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality didn’t heed the evidence, she filed a citizen lawsuit against Formosa with the help of Texas RioGrande Legal Aid in 2017. Two years later, a federal judge agreed that Formosa was a “serial offender” of the Clean Water Act, mandated that it create a $50 million settlement to fund community initiatives and ecological restoration in the area and stop discharging any pellets. Wilson has continued to monitor the bay, and she and others have found violations that have put another $8.4 million in fines into the trust.

With this legal victory under her belt, Wilson is now looking beyond the bay.

“I’m really trying to reach this whole ideal of zero discharge of plastics on a state and national level and even on a global level,” she said, “and to stop the production of plastic plants, which is very near-sighted, and it’s not visionary at all for our communities.”

Receiving the Goldman Environmental Prize emphasizes to Wilson her connection to a larger movement against plastic pollution.

“I’ve come a long way from my small town, small roots thinking,” she said.

At the same time, the prize can turn national and international attention to what is happening in frontline communities like Calhoun County, where air and water pollution from plants like Formosa’s lead to increased cancer risk.

The plant is one of the nation’s leading emitters of vinyl chloride — the carcinogen that sparked alarm when it was released from the train derailment in East Palestine, Ohio, and Wilson receives alerts about emissions every week.

“There’s hardly any way to reach out and get attention on what the issues are down here,” she said.

Subscribe to get exclusive updates in our daily newsletter!

By signing up, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy & to receive electronic communications from EcoWatch Media Group, which may include marketing promotions, advertisements and sponsored content.

233k

233k  41k

41k  Subscribe

Subscribe